KOMPUTER PROGRAMING

Computer programming (often shortened to programming or coding) is the process of designing, writing, testing, debugging, and maintaining the source code of computer programs. This source code is written in one or more programming languages.

The purpose of programming is to create a set of instructions that

computers use to perform specific operations or to exhibit desired

behaviors. The process of writing source code often requires expertise

in many different subjects, including knowledge of the application

domain, specialized algorithms and formal logic.

Overview

Within software engineering, programming (the implementation) is regarded as one phase in a software development process.

There is an ongoing debate on the extent to which the writing of programs is an art, a craft or an engineering discipline.[1]

In general, good programming is considered to be the measured

application of all three, with the goal of producing an efficient and

evolvable software solution (the criteria for "efficient" and

"evolvable" vary considerably). The discipline differs from many other

technical professions in that programmers,

in general, do not need to be licensed or pass any standardized (or

governmentally regulated) certification tests in order to call

themselves "programmers" or even "software engineers." Because the

discipline covers many areas, which may or may not include critical

applications, it is debatable whether licensing is required for the

profession as a whole. In most cases, the discipline is self-governed by

the entities which require the programming, and sometimes very strict

environments are defined (e.g. United States Air Force use of AdaCore

and security clearance). However, representing oneself as a

"Professional Software Engineer" without a license from an accredited

institution is illegal in many parts of the world.

Another ongoing debate is the extent to which the programming language used in writing computer programs affects the form that the final program takes. This debate is analogous to that surrounding the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis[2] in linguistics and cognitive science,

which postulates that a particular spoken language's nature influences

the habitual thought of its speakers. Different language patterns yield

different patterns of thought.

This idea challenges the possibility of representing the world

perfectly with language, because it acknowledges that the mechanisms of

any language condition the thoughts of its speaker community.

History

See also: History of programming languages

The Antikythera mechanism from ancient Greece was a calculator utilizing gears of various sizes and configuration to determine its operation,[3] which tracked the metonic cycle still used in lunar-to-solar calendars, and which is consistent for calculating the dates of the Olympiads.[4] Al-Jazari built programmable Automata in 1206. One system employed in these devices was the use of pegs and cams placed into a wooden drum at specific locations. which would sequentially trigger levers that in turn operated percussion instruments. The output of this device was a small drummer playing various rhythms and drum patterns.[5][6] The Jacquard Loom, which Joseph Marie Jacquard developed in 1801, uses a series of pasteboard

cards with holes punched in them. The hole pattern represented the

pattern that the loom had to follow in weaving cloth. The loom could

produce entirely different weaves using different sets of cards. Charles Babbage adopted the use of punched cards around 1830 to control his Analytical Engine. The first computer program was written for the Analytical Engine by mathematician Ada Lovelace to calculate a sequence of Bernoulli Numbers.[7]

The synthesis of numerical calculation, predetermined operation and

output, along with a way to organize and input instructions in a manner

relatively easy for humans to conceive and produce, led to the modern

development of computer programming. Development of computer programming

accelerated through the Industrial Revolution.

In the late 1880s, Herman Hollerith

invented the recording of data on a medium that could then be read by a

machine. Prior uses of machine readable media, above, had been for

control, not data. "After some initial trials with paper tape, he

settled on punched cards..."[8] To process these punched cards, first known as "Hollerith cards" he invented the tabulator, and the keypunch machines. These three inventions were the foundation of the modern information processing industry. In 1896 he founded the Tabulating Machine Company (which later became the core of IBM). The addition of a control panel

(plugboard) to his 1906 Type I Tabulator allowed it to do different

jobs without having to be physically rebuilt. By the late 1940s, there

were a variety of control panel programmable machines, called unit record equipment, to perform data-processing tasks.

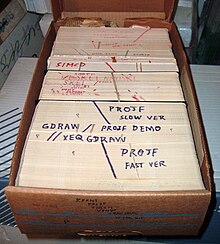

Data and instructions could be stored on external punched cards, which were kept in order and arranged in program decks.

The invention of the von Neumann architecture allowed computer programs to be stored in computer memory.

Early programs had to be painstakingly crafted using the instructions

(elementary operations) of the particular machine, often in binary notation. Every model of computer would likely use different instructions (machine language) to do the same task. Later, assembly languages

were developed that let the programmer specify each instruction in a

text format, entering abbreviations for each operation code instead of a

number and specifying addresses in symbolic form (e.g., ADD X, TOTAL).

Entering a program in assembly language is usually more convenient,

faster, and less prone to human error than using machine language, but

because an assembly language is little more than a different notation

for a machine language, any two machines with different instruction sets

also have different assembly languages.

In 1954, FORTRAN was invented; it was the first high level programming language to have a functional implementation, as opposed to just a design on paper.[9][10]

(A high-level language is, in very general terms, any programming

language that allows the programmer to write programs in terms that are

more abstract

than assembly language instructions, i.e. at a level of abstraction

"higher" than that of an assembly language.) It allowed programmers to

specify calculations by entering a formula directly (e.g. Y = X*2 + 5*X + 9). The program text, or source, is converted into machine instructions using a special program called a compiler,

which translates the FORTRAN program into machine language. In fact,

the name FORTRAN stands for "Formula Translation". Many other languages

were developed, including some for commercial programming, such as COBOL. Programs were mostly still entered using punched cards or paper tape. (See computer programming in the punch card era). By the late 1960s, data storage devices and computer terminals became inexpensive enough that programs could be created by typing directly into the computers. Text editors

were developed that allowed changes and corrections to be made much

more easily than with punched cards. (Usually, an error in punching a

card meant that the card had to be discarded and a new one punched to

replace it.)

As time has progressed, computers have made giant leaps in the area

of processing power. This has brought about newer programming languages

that are more abstracted from the underlying hardware. Although these

high-level languages usually incur greater overhead,

the increase in speed of modern computers has made the use of these

languages much more practical than in the past. These increasingly

abstracted languages typically are easier to learn and allow the

programmer to develop applications much more efficiently and with less

source code. However, high-level languages are still impractical for a

few programs, such as those where low-level hardware control is

necessary or where maximum processing speed is vital.

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, programming was

an attractive career in most developed countries. Some forms of

programming have been increasingly subject to offshore outsourcing

(importing software and services from other countries, usually at a

lower wage), making programming career decisions in developed countries

more complicated, while increasing economic opportunities in less

developed areas. It is unclear how far this trend will continue and how

deeply it will impact programmer wages and opportunities.[citation needed]

Modern Programing